Chemin de Fer

December 6, 2017

I love train timetables. I also love maps, especially road maps, but I get easily confused. Something to do with spatial orientation. But a well-printed (preferably in a tight, cozy agate font) train timetable is a thing of linear beauty, a minimalist’s rendering of the day ahead with a precision down to the minute hand on your watch.

I’m soothed by the quiet confidence and assurance a timetable presents. Utterly devoid of the boastfulness of, say, someone who can recite pi out to twenty-seven digits, a train timetable modestly and straightforwardly breaks down a day’s journey into bite-sized chunks of departures and arrivals that you sometimes find yourself wishing could be applied to the guests visiting you in your home. The only reason the cliché “if I could do it all over again” holds up over time is because there exists the train timetable that would show you precisely how it would get done over and over again, out to two digits.

To me, if I may carry these analogies to the limits of interest and tolerance, the train timetable is the medical chart of a living thing in for a checkup. The station is the patient, the big station clock ticking is its heart, the trains are the lifeblood pumping healthily in time with its heart all along the arteries (departures) and veins (arrivals) of the great steel rails. And we are but mere corpuscles flowing along the train tracks of life. All right, I agree, enough of vaulting attempts to elevate iron and steel into couplet and verse.

I don’t do crosswords or puzzles of any kind, but I can sit in heavenly bliss dissecting a timetable into multiple connections of a day’s travels. The game might be to see how many connections can be made with the least amount of layover in between. Given the way I’ve “organized” this trip that may mean arriving in Bordeaux instead of Toulouse, or Tours instead of Nantes. What do I care? It will make a fonder memory that I took six trains with only twenty-minute or less layovers to get to Lyon, instead of trying to recall what the cathedral there looked like and how it differed from any of the other gazillion that exist in France.

Once, when rotating in The Eye in London, Carolyn chastised me for intently perusing a map of the city, instead of taking in the dazzling views of the actual city the ocular Ferris wheel was providing. She had a valid point. Yet, it seemed more compelling to me to locate what I was glancing at through the glass enclosed compartment in relation to the rest of the sprawling metropolis depicted in my tourist map, than to soak in the majestic Houses of Parliament and Big Ben staring me right in the face. I guess it’s just my bookish nature.

As you can deduce, Carolyn had her work cut out for her when we began traveling together. The pattern that emerged is that we’d amble along a pleasant street and then I’d stop and wait in the fifty or hundred feet that had opened between us like an accordion to close back up. Later, at a café, she’d show me the photos she’d taken while I’d waited for her.

“Wow,” I would say. “That’s great. Where’d you get that one?”

“We passed it on our walk.”

And so it would go.

All this is by way of saying, what you can expect from these dispatches is an exhaustive, if not exhausting treatise on the on time departures and arrivals of the French Railway. What you should not expect are well composed shots of the land and the people traversed by that rail system.

Maybe, instead, a shot or two of an eye-catching arrival and departure tote board, or the sandwich case of an inviting food kiosk amidst the bustle in the terminal.

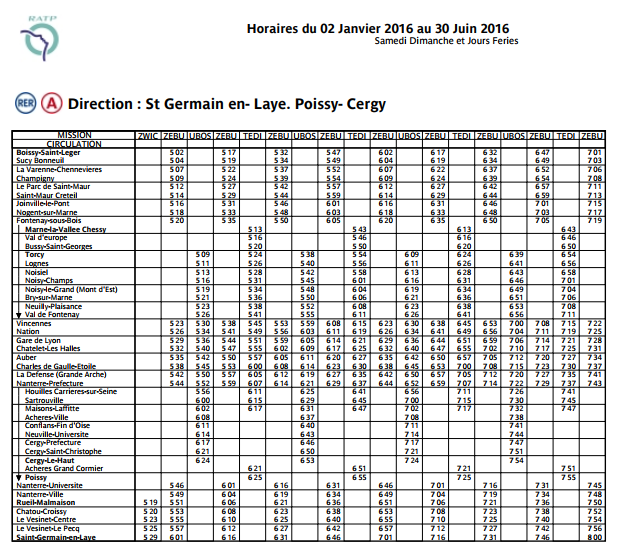

Paris Rail Timetable; January-June 2016

Be the first to comment