Good morning America

December 12, 2019

This is an internet stock photo, because it never occurred to me to ask Carol to photograph any of the half-dozen or so junkyards that passed our train window

Amtrak #5

The City of New Orleans

Riding on the City of New Orleans

Illinois Central, Monday morning rail

Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders

Three conductors and twenty-five sacks of mail

Note it does pull out of Kankakee

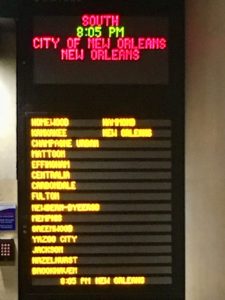

Carol and I boarded Amtrak’s #59, still known as The City of New Orleans, on a Monday, but not in the morning. There were eleven cars. There would be three sets of only two conductors each for the trip to New Orleans. There were 218 passengers. The train no longer carried mail. In short there wasn’t much still in common with Arlo Guthrie’s ballad, except this: Guthrie released his version of the song in 1971, and the cars we were riding in dated back to the 1970s.

All along the southbound odyssey

The train pulled out at Kankakee

And rolls along past houses, farms and fields

Passin’ trains that have no names

And freight yards full of old black men

And the graveyards of the rusted automobiles

Although the train itself had changed much since it’s musical tribute, the America we saw from the dirty and smudged Amtrak windows hadn’t. We still pulled in and out at Kankakee, albeit at night. We rolled along past houses, farms and fields, but I suspect many more had become dilapidated and boarded up than when Guthrie had sung about them. And, oh yeah, we passed many a graveyard of rusted automobiles, probably a lot more than was here in 1971.

Good morning, America

How are you?

A house in Mississippi on the “other side of the tracks”

Say don’t you know me? I’m your native son

I’m the train they call the City of New Orleans

And I’ll be gone five hundred miles when the day is done

“The train no longer carried mail. In short there wasn’t much still in common with Arlo Guthrie’s ballad, except this: Guthrie released his version of the song in 1971, and the cars we were riding in dated back to the 1970s.”

Yet, Carol and I were enjoying the ride, her second and my eighth aboard America’s anachronistic and almost cynically maintained passenger rail service. I find the staff almost uniformly both helpful and cheerful to an unctuous degree, and even the elimination of a full service kitchen and dining car still left us with three hot meals for our 19-hour trip that remained a cut or so above the food served in coach class on an airplane. Our first class bedroom berth included a complimentary glass of wine at dinner, as well as our own private bathroom. We had all the comforts of home, as long as your home occupies only slightly more than the square-footage of an ADA-sized port-a-potty.

Nighttime on the City of New Orleans

Changing cars in Memphis, Tennessee

Half way home, we’ll be there by morning

Through the Mississippi darkness

Rolling down to the sea

But all the towns and people seem

To fade into a bad dream

And the steel rails still ain’t heard the news

The conductor sings his songs again

The passengers will please refrain

This train has got the disappearing railroad blues

The native son

The nights and days are reversed, and there were no changing of cars, but we were just about halfway home, as we pulled into Memphis the following morning. As we rolled through the Mississippi sunshine, Carol saw cotton fields for the first time. I told her I could only hope the field hands were issued W-2s nowadays, and the foremen carried maybe a clipboard and a watch, instead of a bull whip. Outside of that cinder of social progress, Mississippi not only looked the way it always has, but there was also a sense that it still strove as a state to keep things just that way forever. My guess was that our tracks still described the boundary between the white and black neighborhoods of the towns that did seem to be fading into a bad dream.

We arrived ahead of schedule into New Orleans’s Union Passenger Terminal – not bad for Amtrak. We stood in the warm afternoon, refreshed by a good night’s sleep, good meals, and the still existing leisure of train travel in the United States. But the sense of something dying was strong in the slightly humid afternoon. I looked back at the terminal before hopping into our Uber, and thought: Arlo got this part exactly right, the disappearing railroad blues hung melodic but deeply sad in the heavy air outside the station. One day – a day that may come in my lifetime – I couldn’t help feeling that these steel rails will finally hear the news.

Be the first to comment