BOOK REVIEW: The Year of Magical Thinking

May 30, 2018

The Year of Magical Thinking

by Joan Didion

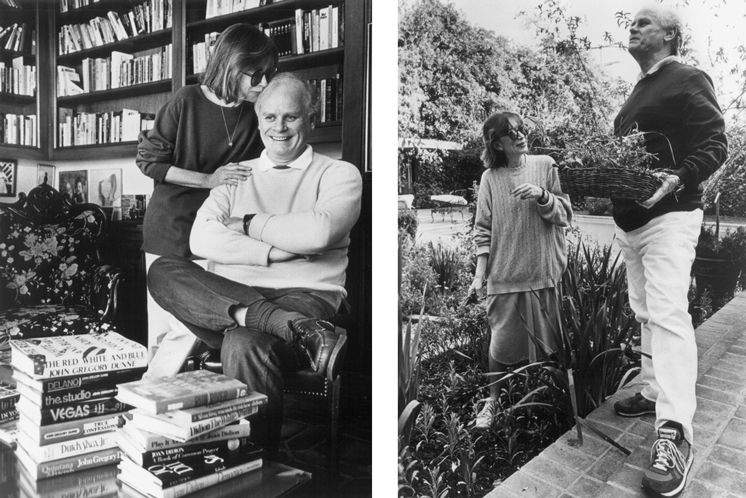

Didion and Dunne

The theme that emerges from these pages is “control.” Control, as in to make the tragic events of the sudden death of a spouse of forty years to “unhappen.” This, of course, is what we all face, waking up that first day as a widow or widower. It’s the shock, the denial, the grief, even the self-pity that we all experience in those first days of mourning.

It’s in the hands of a skilled writer, one adept at both thorough self-examination and the ability to express it on paper lucidly and convincingly that makes The Year of Magical Thinking a must read for those who truly want to comprehend the unbearable pain they are going through and can’t seem to get beyond.

On December 30th, 2003, Didion is faced with two incomprehensible tragic events: the near-terminal illness of her only daughter Quintana, and the sudden death of husband John Dunne, as they sat at the dinner table following a visit to the hospital’s ICU. “John was talking, then he wasn’t.”

Didion wrote a few days later: Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends… What then ensues is Didion’s almost forensic examination of the emotional upheaval she went through in what she immediately understood as her attempt to unspool time and make it so that John doesn’t die. Hence, the title.

I see now that my insistence on spending that first night alone was more complicated than it seemed, a primitive instinct. Of course I knew John was dead. Of course I had already delivered the definitive news to his brother and to my brother and to Quintana’s husband. The New York Times knew. The Los Angeles Times knew. Yet I was myself in no way prepared to accept this news as final: there was a level on which I believed that what had happened remained reversible. That was why I needed to be alone… I needed to be alone so that he could come back. This was the beginning of my year of magical thinking.

With the kind of intellectual detachment that may turn some readers off (the kind that might rather indulge the self-pity that brings them to those syrupy, semi-religious homiletic tomes with covers of soothing dawns or sunsets) Didion creates more of a manual for confronting face-to-face the utter irrationality of not accepting the death of a spouse,and the expectations of actually bringing them back, without the shame or self-pity.

The key for Didion’s eventual acceptance and path back to emotional health (Quintana does make a full recovery, but only after additional near-tragic developments) comes after experiencing what she describes as the “vortex.” Didion first references Freud’s “work of grief,” the capacity to confront a living memory and realize and accept it’s now part of a dead past and not the living present. She quotes Freud: “It is remarkable that this painful unpleasure is taken as a matter of course by us.”

That this unpleasure is not taken as a matter of course by Didion is the crux of the book. But she comes to the realization she must let go and let the dead be dead if she is to live her own life. At the end of Magical Thinking, though, she still sees letting go as a betrayal of their life together, Didion’s last lines contain the seeds of her eventual acceptance.

“I think about swimming with him into the cave at Portuguese Bend, about the swell of clear water, the way it changed, the swiftness and power it gained as it narrowed through the rocks at the base of the point. The tide had to be just right. We had to be in the water at the very moment the tide was right. We could only have done this a half dozen times at most during the two years we lived there but it is what I remember. Each time we did it I was afraid of missing the swell, hanging back, timing it wrong. John never was. You had to feel the swell change. You had to go with the change. He told me that.”

This book was written by a writer, which, as a writer, hit home for me. By nature we are self-absorbed, so loss and grieving are going to affect us in the most self-referential and self-indulgent ways. So, if writers can find a way to cope and ultimately go on to live their lives following a tragic loss, there should be plenty of hope that all ultimately can and will.

Images from A Year of Magical Thinking

Be the first to comment